According to Sheryl Brahnam, professor in the Department of information technology and cybersecurity at Missouri State University, who compared video conferencing to highly processed foods, “In-person communication resembles video conferencing about as much as a real blueberry muffin resembles a packaged blueberry muffin that contains not a single blueberry but artificial flavours, textures and preservatives” (Why Zoom is Terrible, New York Times, 29 April 2020).

Like our professor’s muffins, what is the taste our online project meetings have lost? Thinking about my experience in these late months, I would answer that online our level of critical interaction – notably discussion and debate – has dramatically decreased. The greater the number of participants, the lower the quantity and, above all, the quality of their mutual communication.

Do you remember the old, ordinary Transnational Meetings in presence? They are conceived – and they have always been – as moments of strong exchange, designed to help the partnership to improve the project implementation and to solve the most critical issues. After the speeches in agenda, usually the participants try to get the most from the opportunity they have to work shoulder-to-shoulder with their colleagues. Moreover, working together is an opportunity to reaffirm and strengthen the “organisational culture” of the group and its project. The debate is often lively and its quality remarkable, as people are strongly focused on the topics being dealt with. Sense of personal belonging and mutual control promote concentration, listening and providing feedback.

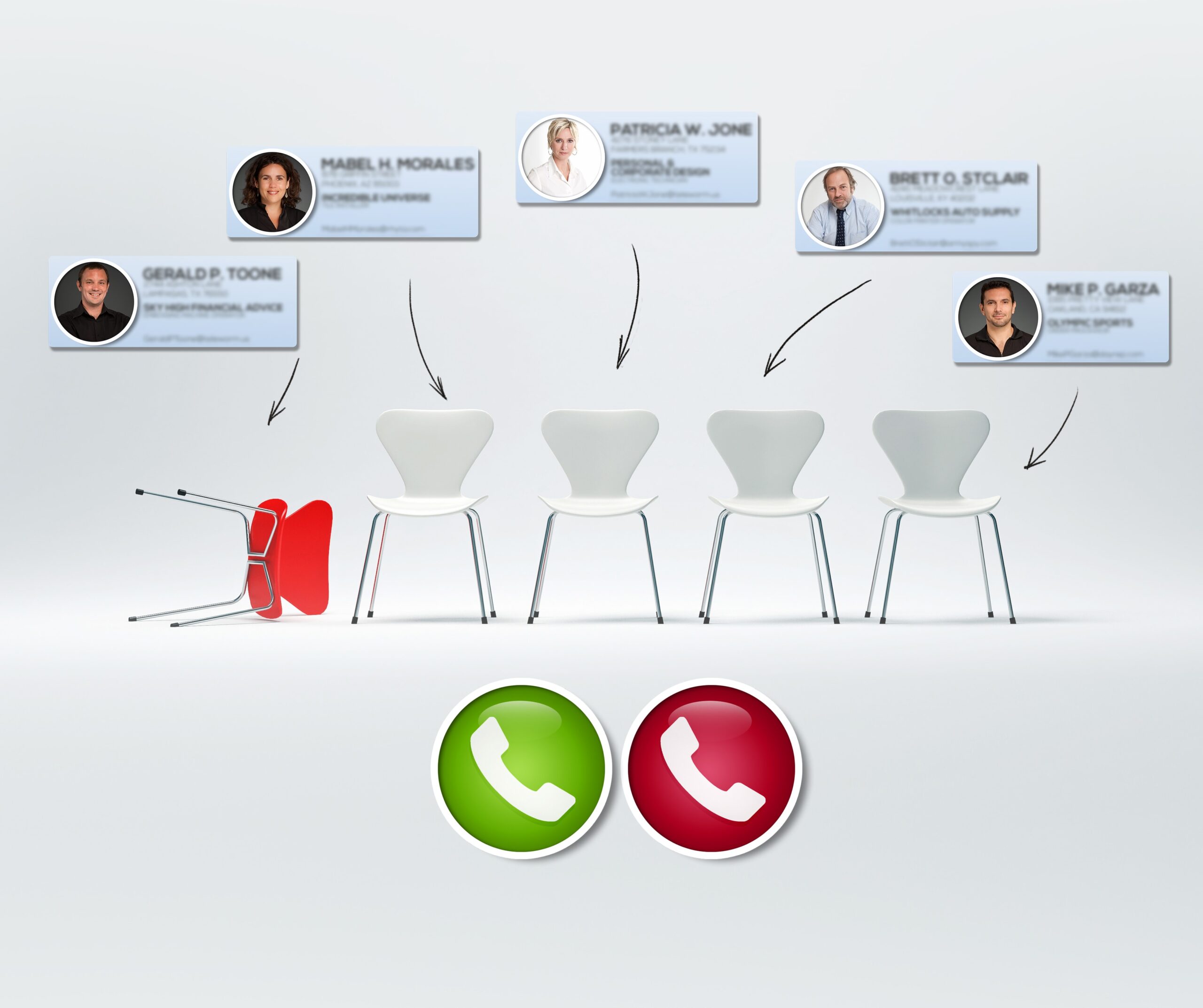

How do the group dynamics change when people meet online?

The more an online session is attended – but even 20 members are enough in this context – the more every individual participant feels being alone and anonymous. And they actually are. Muting microphones and turning off cameras to facilitate internet connection may be a further attack to involvement and concentration, so letting our multitasking attitudes prevail: we listen to the speakers while reading and sending emails, scrolling WhatsApp chats, flipping through online newspapers, working on another project. The speakers, too, find themselves isolated, talking to people who do not look them in the eye, even when the camera is on, because depending on the camera angle, people may appear to be looking up or down, or maybe because they are looking at themselves on the screen.

A poor quality of listening compromises interaction. How can we intervene timely, develop appropriate and articulate concepts, lay the foundations for a critical rethink of the collective work if we have listened little and badly?

Time has come to reverse this trend. Sedentariness is not good for our projects. Nor for us, who are a little farther away every day. With our minds, as well as our bodies.