The importance of retention of information which leads to knowledge is addressed in this article. Hints and strategies to improve this memory process are described along with the good reasons for doing so. Businesses might thus make the best out of a learning course and educators might improve their training abilities.

You invest in your employees—mentoring, conferences, training. Yet over time, unused knowledge fades. Employees take other jobs. How do you protect your investment?

Marketing had the highest turnover rate (17%) of any profession in 2018. It isn’t the only cause of knowledge loss. Retirements, promotions, intracompany transfers, and “the forgetting curve” all play a role, too.

But the consequences of those events aren’t inevitable. Knowledge retention is a process for identifying:

critical knowledge that is at risk of loss, prioritizing what is at risk based on potential knowledge gaps and their impact upon overall organizational performance, and then developing actionable plans to retain that knowledge.

Knowledge retention isn’t a corporate nicety. It’s a “critical strategic resource” and the basis for a sustainable competitive advantage. Successful knowledge retention programs answer three key questions:

- What knowledge may be lost?

- What are the consequences of losing that knowledge?

- What actions can be taken to retain that knowledge?

This post helps you answer each.

Why knowledge retention matters

“Let me tell you a story,” began Jim Palmer, a partner with e-learning developers LeanForward. While at a previous company, Palmer and several coworkers were asked to gauge their company’s market position. What would it take for a competitor to steal their business?

Teams spent days crunching numbers. When everyone presented their findings, one team had a shockingly low estimate: $200,000. How? They planned to hire away the company’s master developer for $200,000 a year. The plan would cripple the business and empower an otherwise feeble competitor.

Knowledge retention makes information transferrable. It moves knowledge from the head (or hard drive) of a single employee into an accessible, company-owned repository. That transferability is a competitive advantage:

- Critical knowledge stays with the company, not the employee.

- New employees are onboarded more quickly.

- Current employees access the knowledge they need more efficiently.

Smaller businesses have an even greater stake in knowledge retention: “they are often more vulnerable than larger organizations in terms of losing key personnel.”

At the same time, implementing knowledge retention programs is usually easier for smaller companies: A few Google Drive or Dropbox folders may make knowledge accessible for the 20 employees who need it.

Strong knowledge retention programs transfer ownership. Individuals use corporate knowledge rather than corporations using individual knowledge.

Achieving that inversion isn’t easy.

What makes knowledge retention so hard?

Most businesses start too late. A one-hour exit interview of an employee who’s been with the company for 10 years will capture a fraction of their knowledge.

Nor is the knowledge loss limited to technical knowledge:

It is not simply losing someone’s knowledge if they retire or leave the organization, it is also losing their social network, if you will, in terms of who they seek out for answers to questions in their domain.

That potential loss also includes email chains, Slack threads, niche websites, bookmarks, search patterns, etc. An old email chain may explain how to retain a long-term client. Or a bookmarked website may explain the rationale behind an internal dashboard.

For high-value employees, there’s also the knowledge-engineering paradox: The greater the expertise, the harder it is to extract that knowledge. Expert opinions don’t distill into a simple checklist.

Even without employee turnover, other challenges undermine the preservation and sharing of knowledge.

The forgetting curve

When we surveyed hundreds of marketing leaders, many noted a similar challenge: measuring knowledge retention and application from training.

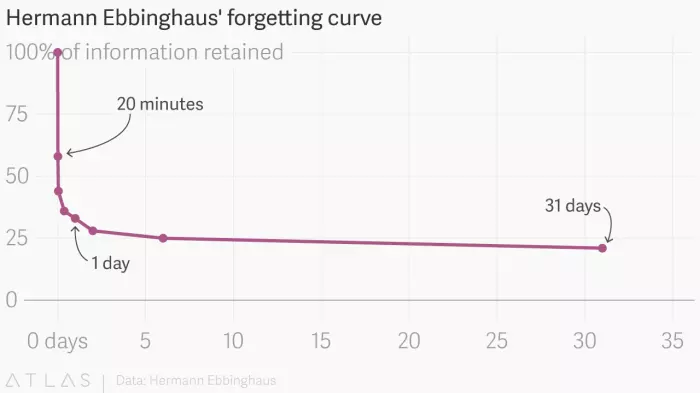

The forgetting curve plots the decay of human memory:

As Palmer explained, knowledge retention improves if you “compact the time between delivering training and applying it.” Once you begin applying knowledge, retention is self-sustaining.

Palmer also noted that some trainings (e.g. CPR, sexual harassment) don’t have an explicit “time until application.” Without knowing when the training will be needed, the solution is regular refresher courses.

These knowledge retention challenges have solutions. Each solution starts with a knowledge audit.

Where to start: The knowledge audit

A knowledge audit answers the first two questions about knowledge retention:

- What knowledge may be lost?

- What are the consequences of losing that knowledge?

How to inventory knowledge

As Jay Liebowitz details in his book, Knowledge Retention: Strategies and Solutions, smaller companies can inventory existing knowledge with a three-question survey:

- What specific area of knowledge do you have?

- Is there a backup expert in this area? If so, who is it?

- On a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high), how important is this knowledge to the company’s strategic vision?

Those questions are a starting point. Yet not all critical knowledge will surface. An in-depth audit tackles two key sources for knowledge retention:

- The decision-making process;

- Internal social networks.

The decision-making process

The best way to extract knowledge used in decision-making is to reverse engineer the process. Engage employees in backward-looking interviews or surveys about how they make decisions:

The process identifies which resources employees use most often when they make good (or bad) decisions.

You can also identify key sources of knowledge with more general questions:

- Which websites do you visit most often to answer work questions?

- Which email newsletters are most valuable to personal growth?

- Which books have influenced your work?

Internal social networks

Internal social networks are often overlooked during knowledge audits. If you faced a big decision today, whom would you consult first? Why?

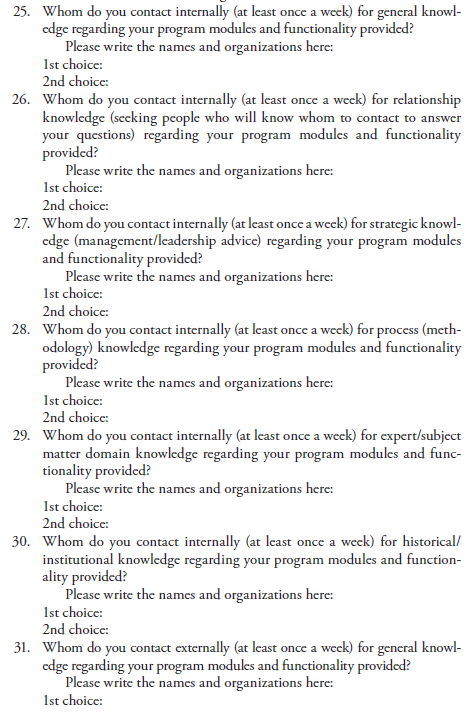

As Palmer has found, audits of internal social networks reveal patterns: “There were certain things where, every week, people were asking the same person about the same topics.”

If you expand the line of questioning, you can identify social networks within your company that a single employee—due to turnover, internal transfer, or retirement—could destroy.

Knowledge audits of social networks should extend beyond employees’ in-the-moment job needs:

- Whom do they consult for technical or historical company knowledge?

- Whom do they go to for task-specific or general knowledge?

- Where do they get essential knowledge for decision-making or personal growth?

Common mistakes with knowledge audits

Two assumptions can undermine results:

- Assuming that critical knowledge exists only with subject-matter experts. Administrators may know how to solve logistical challenges quickly, like the right number to call when the Internet cuts out.

- Assuming that everyone will want to share their knowledge. Some employees may hoard knowledge to try to seem irreplaceable or get a raise. Incentives may encourage knowledge sharing.

The outcome of the knowledge audit

The outcome of a knowledge audit, Liebowitz details, is a rating scale based on the “attention factor.” The Attention Factor identifies the most critical knowledge within a company:

Attention Factor (AF) = Knowledge Severity (KS) × Knowledge Availability (KA)

Where:KS = criticality of the knowledge to the strategic mission of the organization (on a scale from 1 [low] to 10 [high]).

KA = availability of the knowledge based upon whether an expert (E) exists in the organization (1 = yes; 0 = no) and the likelihood (LE) of the expert leaving the organization in the next 5 years (on a scale from 1 [low] to 10 [high]). The aggregate KA score would be computed as E × LE.

The maximum AF score is 100. The higher the score, the greater the need for knowledge retention.

After you score information from the audit, you can put processes in place to safeguard knowledge and make it more accessible.

Ways to improve knowledge retention

Not every solution is complicated. Pfizer increased efficiency by 15% with a simple note-taking program. The process to identify a solution is two-part:

- Strategy. Build knowledge retention into the company culture from day one, not the last day, of an employee’s tenure.

- Tactics. Choose how to store and distribute knowledge. Safeguard it from employee turnover and protect investments from employee training.

Keys to a successful knowledge retention strategy

Liebowitz identifies four pillars of a knowledge retention strategy:

- Recognition and reward structure. Knowledge retention must be part of the everyday life of employees. Reward employees for participation in knowledge-retention activities. Awards for mentorship (carrot) or requirements for promotion (stick) may help.

- Bidirectional knowledge flow. Holders of key knowledge aren’t always the highest paid people in the company. Top-down knowledge retention strategies don’t work, especially in tech-heavy companies in which younger employees may have unique savvy.

- Personalization and codification. These two components are not mutually exclusive. Personalization refers to ways to exchange knowledge with other employees. Codification is how knowledge is stored.

- The Golden Gem. If you missed the opportunity to capture knowledge from past employees, bring back retirees for lunch-and-learns or as consultants. (The strategy is a key part of NASA’s knowledge retention program.)

To succeed in each component of the strategy, you’ll need several tactics.

Knowledge retention tactics

Where to store information

Cheat sheets and informal repositories. A knowledge audit can identify existing “cheat sheets” or locations of critical information (e.g. Dropbox folders). Organizing that information may be as simple as creating a spreadsheet with links to materials.

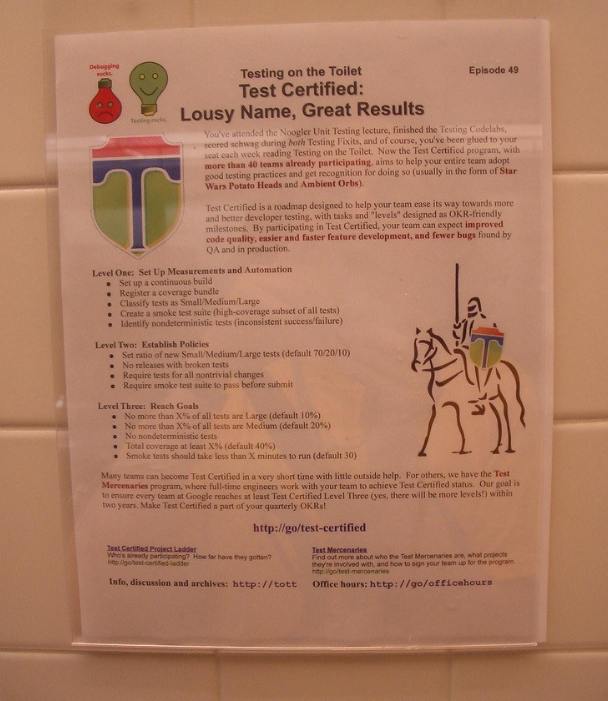

There are more creative solutions, too. In 2007, Google wanted to encourage engineers to run more tests. They created “Testing on the Toilet,” a weekly program of knowledge sharing via printed flyers on the interior of bathroom stalls.

Wikis, intranets, and company bibles. Unorganized folders of documents won’t scale for large organizations. In the late 1990s, Fiat Chrysler (then Daimler Chrysler) pioneered a method of knowledge retention on engineering their vehicles. The result was a 5,000-chapter electronic resource, with contributions from nearly as many authors. Airbus later took on a project.

Internal wikis (made possible by one of several platforms) and intranets are modern equivalents. Google’s MOMA shares info on current projects and recommends lunch spots. (There is, of course, a risk of security breaches, even for Google.)

Tettra, Guru, and Atlassian’s Confluence support knowledge sharing within teams. All have Slack apps to pass data between platforms. For example, you can search for and share the answer to a common question—stored in Tettra—within Slack.

Oral history and storytelling. Events also have a role in knowledge retention. Weekly lunch-and-learns or recaps of critical moments in company history can illuminate keys to decisions and processes that don’t fit neatly into guides.

These sessions also offer participants a chance to ask follow-up questions.

Mentoring. Identifying mentors and mentees hinges on two questions:

- Which employees hold knowledge with the highest “attention factor”? They should be mentors.

- Who would benefit most from that knowledge? They should be mentees.

After-action reviews. After-action reviews create a knowledge base of “lessons learned.” In agencies, “post-mortems” on departed clients identify early warning signs of client departure or recurring service failures.

After-action reviews are sources of knowledge and opportunities to identify knowledge gaps. What information, if teams had access to it, could’ve improved the outcome?

The value of a knowledge base depends on how often employees use it.

How to encourage employees to use company knowledge

A valuable store of company information doesn’t guarantee knowledge retention:

- What will motivate employees to use it?

- How should you present the information to maximize retention?

The tactics that improve any type of learning apply to knowledge retention:

Use engaging learning methods. Can break-out groups encourage more participation? Is there a way to create training scenarios? Can the knowledge be applied to an existing project?

Make knowledge easily accessible and digestible. Is content available on mobile devices? Is knowledge retention isolated to one-off learnings, or is it integrated into a learning campaign? Are there opportunities for “microlearning” that fit into employee schedules?

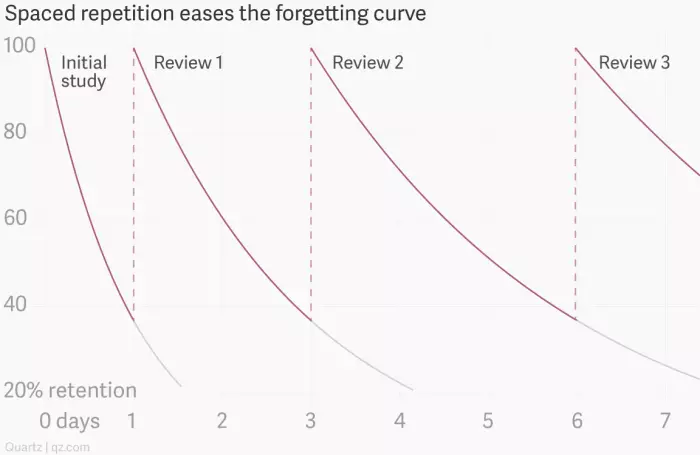

Use spaced repetition. What is the gap between learning and applying knowledge? Spaced repetition plots ideal times for reinforcement to improve retention. (Shorter intervals are not always better. Bees, for example, learn more effectively with training at 10 minute intervals compared to those of just 30 seconds.)

Synchronous learning (i.e. live, instructor-led training) often has a longer gap between delivery and application. Everyone receives training at the same time, regardless of when they may apply it. Asynchronous learning can reduce those gaps. Employees take training courses immediately prior to use based on individual schedules.

Measuring knowledge retention and application

In a perfect world, companies skip over the measurement of knowledge retention. Instead, they measure knowledge application. “The most important thing,” Palmer reiterated, “is behavior change or applying that information.”

There are a near-infinite number of ways to measure application. For example, in marketing departments:

- Is the onboarding time for new employees reduced?

- In agencies, can analysts take on a full client load more quickly?

- For in-house marketers, can new employees’ campaigns match outcomes of seasoned employees more quickly?

- For department-wide training, are post-training campaigns launching more quickly? Are the results better?

Often, Palmer conceded, clients aren’t ready to measure application. For example, they may not have historical data to compare onboarding times. In those cases, measuring knowledge retention becomes the primary method.

Measuring retention typically takes the form of quizzes, surveys, or skill checks. As Jack Phillips details, all measurement comes at a cost. A full calculation of ROI is possible, but it may be necessary—or undermine the very ROI it seeks to measure.

Conclusion

Most business owners will tell you that their employees are their most valuable asset.

Yet, too often, that asset is unprotected. Individual knowledge remains precisely that, vulnerable to an employee departure or at risk of fading over time.

Knowledge retention is a three-part process:

- A knowledge audit to identify critical knowledge;

- The selection of strategies and tactics to make that knowledge accessible and engaging;

- A plan to measure the impact of knowledge retention or application.

Without knowledge retention, new hires and training programs merely sustain—or try to rebuild—past knowledge. A successful strategy, in contrast, ensures the same outcome you seek throughout your business: growth.